The theory that echidnas and platypuses descended from an aquatic ancestor has long been hotly debated, but now scanning technologies have delivered the first fossil evidence to support it.

Headed up by palaeontologist Emeritus Professor Suzanne Hand from UNSW’s School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, micro CT scanning has given research into a fossil found 30 years ago a new lease on life.

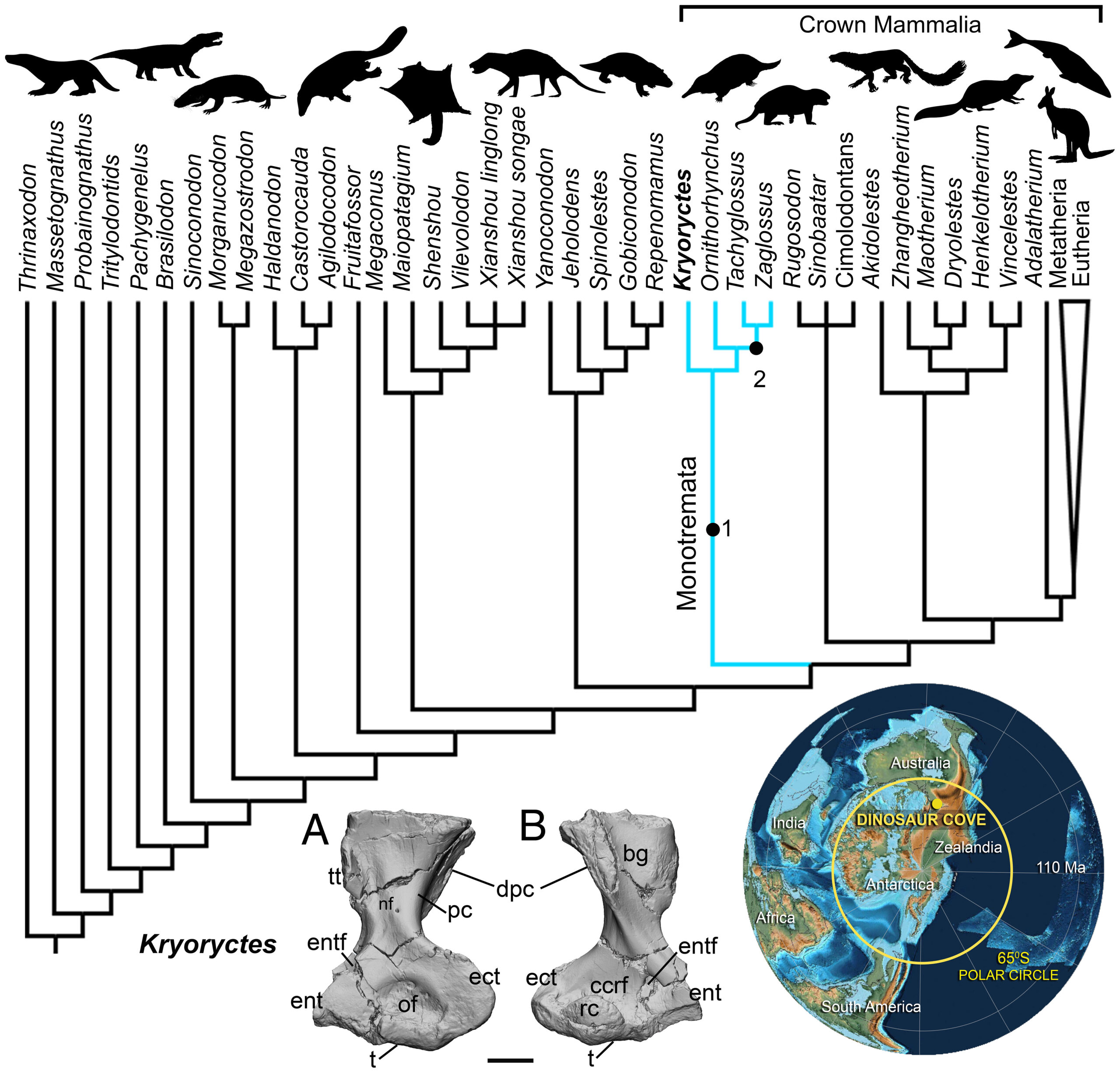

Despite their differences, the platypus and four echidna species are the sole living representatives of egg-laying mammals (monotremes). Their ancestors are poorly known but include the now-extinct, 108 million-year-old Kryoryctes cadburyi.

The scans revived dialogue about the ancestors of monotremes. Were ancestral monotremes such as K. cadburyi land-dwelling like the echidna, or semiaquatic like the platypus?

The scans suggest that K. cadburyi was semiaquatic, despite the rarity of aquatic mammals evolutionarily returning to the land.

Scans revealed internal structure of fossils

Prof Hand explains that she has been using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) since the early 1980s, but micro CT had enabled her research to expand significantly.

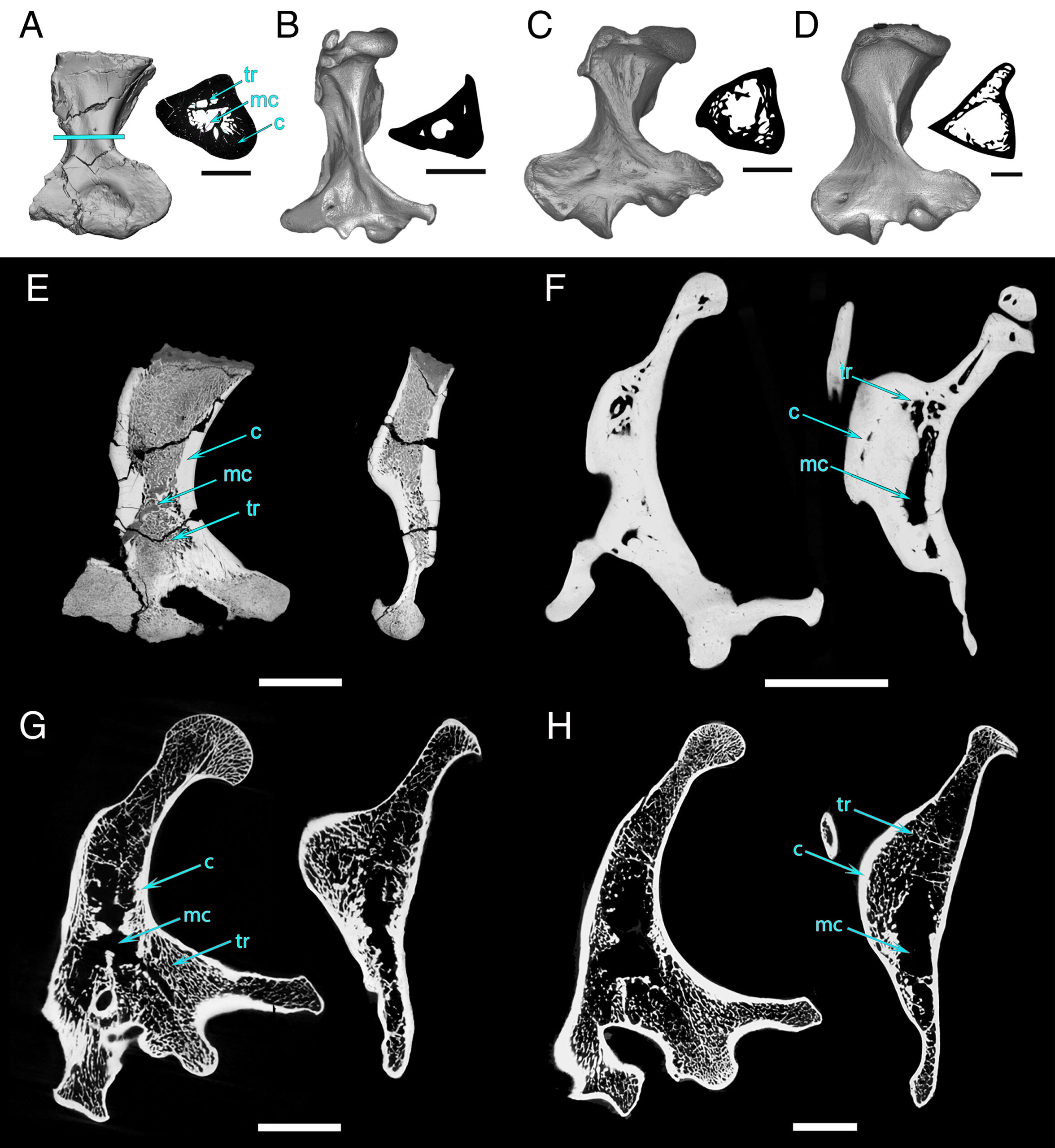

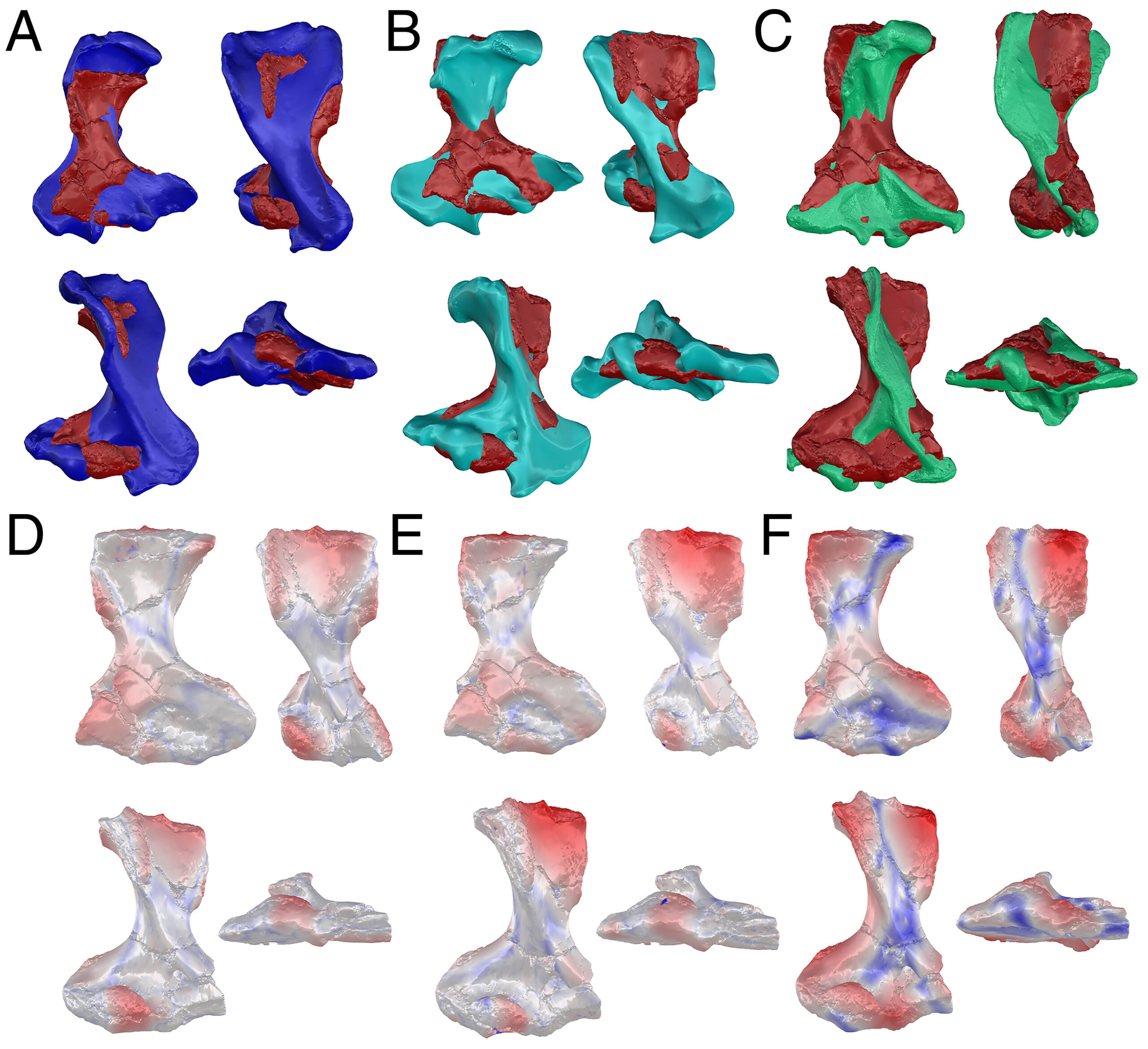

“Knowing the external structure of a bone allows you to directly compare it with similar animals to help work out relationships, but seeing the internal structure reveals other clues – we can ask questions about how animals lived,” Prof Hand says.

Monotremes have a very incomplete fossil record, making the 5-cm-long humerus bone of K. cadburyi crucial to understanding how monotremes evolved.

“In the past, any paleohistology techniques to see inside fossils tended to be destructive; for example, taking cross-sections from the central part of the bone. But now with micro CT, neutron CT, micro PET and Heliscan you can visualise internal structures without causing damage.”

ANSTO instrument scientist Dr Joseph Bevitt says that echidnas and platypus are “truly enigmatic creatures”, distinct from all other animals living today.

“This research provides an insight into the origin and evolution of these species, helping us understand how they have adapted to survive in Australia,” he says.

Looking inside has revolutionised palaeontology

The fossil looked more like an echidna from the exterior, says Prof Hand, but after applying many different scanning methods, the team found its interior looked more like that of a platypus.

“From these bone microstructures, we can extrapolate that K. cadburyi was semiaquatic and sometime in its history, the ancestor of the modern echidna has returned to land,” said Prof Hand.

Platypuses have solid bones which are not very efficient to move about on land. They have thick bone walls – acting like ballast in water – and a small central cavity. Echidnas have lighter bones, more like honeycomb, with thinner bone walls.

“This is really extraordinary because there are many instances in the fossil record of mammals that go from land to water, like seals, whales, otters and walruses, but from water to land is rare. Echidnas have had this ability to adapt, and they are surviving probably better than platypuses.”

“Visualising the internal structure of bones in a non-destructive way has revolutionised palaeontology, and it is especially exciting and important in understanding the evolution of this group of mammals that we know the least about.”

NIF facilities and experts “absolutely essential”

“NIF facilities were instrumental in making this research happen,” says Prof Hand.

“But it’s not all about machines – it’s definitely the people as well – they are amazing,” she says.

“The scientists operating the machines are absolutely essential with the experience and knowledge that they bring. They are patient, insightful and also lateral thinkers, and they apply knowledge from other disciplines to your discipline.”

Prof Hand initially brought samples to UNSW NIF Facility Fellow Dr Tzong-Tyng Hung for preliminary scanning. Dr Hung – who assists researchers in planning, imaging and initial analysis – helped the team examine the data so they could explore the possibilities from the revealed internal structures. From there, Prof Hand’s team moved to other instruments to capture higher resolution images of the fossil.

“Over time, Sue’s brought a lot of different samples to me. We can do very quick scans for them – as opposed to the ultra-high resolution scanners that take hours and cost 5–10 times more,” says Dr Hung. “Our work is a great way to screen samples, catalogue them, and allow researchers to prioritise which samples to further investigate.”

The collection of fossil and comparative specimens were scanned using:

- Siemens Inveon MicroPET/CT scanner in the Biological Resources Imaging Laboratories, Mark Wainwright Analytic Centre, UNSW Sydney – a node of the National Imaging Facility

- Xradia MicroXCT scanner at Monash University, Melbourne

- the ‘Dingo’ thermal-neutron imaging instrument at ANSTO, Sydney – a National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS) capability – an instrument that Dr Bevitt says has “been used for extraordinary insights into mammal evolution”

- Thermo Scientific HeliScan II microCT system, part of UNSW Sydney’s core facilities in the Tyree X-ray Micro-CT Facility.

Behavioural questions can be asked using scanning

“Scanning techniques to look inside fossils have opened up a world of new opportunities in palaeontology,” said Prof Hand.

“From the structure of bones we can start to ask questions like – did these animals have a fast or slow metabolism, did they hibernate, did they experience food shortages?”

Imaging the structure of bones can show up lines of arrested growth, like tree rings, which tell us about interruptions in growth caused by various factors, such as disease, malnutrition, or seasonal changes in the environment.

“We are using all the technology available – neutron scanning, CT, SEM and helical scanning – which all provide different types of information to solve the puzzle.”

This research was published in PNAS.